My Master Thesis

Misc ·In this blog I will make a summary about my Master thesis: Learning to Plan in Large Domains with Deep Neural Networks (pdf), in case someone is interested.

Contents

- Before We Start

- Motivation

- Revisit of AlphaGo Zero

- Neural Networks that Learn from Planning

- Experiments

- Conclusion

Before We Start

Before we start, I would like to give you some insight on my master thesis. In short, my thesis is basically an extension of AlphaGo Zero inspired by Imagination-Augmented Agents.

If you have already read the above two papers, you will find my thesis quite easy to follow. If not, well, I cannot guarantee anything. In the following sections I assume you have a general understanding of how AlphaGo Zero works, e.g.:

- A neural network with a policy head and a value head,

- Monte-Carlo tree search (MCTS) to find the best action,

- How neural network estimation is combined with MCTS in AlphaGo Zero,

- Selfplay to sample training data,

- Loss function in AlphaGo Zero and its optimization.

Motivation

In the domain of artifcial intelligence, effective and efficient planning is a key factor to developing an adaptive agent which can solve tasks in complex environments. However, traditional planning algorithms only work properly in small domains:

- Global planners (e.g. value iteration), which can in theory give an accurate esimation of all states, suffers from the curse of dimensionality.

- Local planners (e.g. MCTS), which gives a coarse estimation of the current state, becomes less effective in large domains.

On the other hand, learning to plan, where an agent applies the knowledge learned from the past experience to planning, can scale up planning effectiveness in large domains.

Recent advances in deep learning widen the access to better learning techniques. Combining traditional planning algorithms with modern learning techniques in a proper way enables an agent to extract useful knowledge and thus show good performance in large domains. For instance, AlphaGo Zero achieved its success by combining a deep neural network with MCTS.

However, in the above example, the neural network does not fully leverage the local planner:

- Only the final output of the local planner (e.g. the searching probability distribution) is relevant to the agent’s training.

- Some other valuable information of the local planner (e.g. the trajectory with the most visit count) is nowhere to be used.

Hereby we raise the following question: is it possible to design a neural network that can fully leverage the local planner to further improve the effectiveness and efficiency of planning?

Revisit of AlphaGo Zero

Let’s first revist some key parts of AlphaGo Zero.

Neural Network Architecture

The neural network in AlphaGo Zero can be formed as:

where

- $ s $ is the input state,

- $ p $ is the output policy,

- $ v $ is output value.

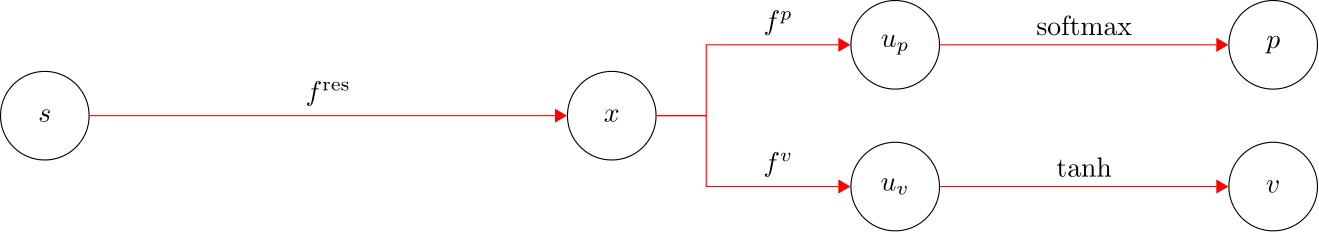

Fig. 1 provides a more detailed description. The state $ s $ is first encoded into some feature $ x $, and then the network is split into two heads: a policy head to estimate the policy $ p $ and a value head to estimate the value $ v $.

Principal Variation in MCTS

AlphaGo Zero relies on MCTS to find the best action of the current state. In AlphaGo Zero, tree searches prefer action with a low visit count $ N $ and a high prior porbability $ p $, which is a tradeoff between exploration and exploitation. The action with the highest visit count will be selected after the tree search reaches a pre-defined depth $ k $.

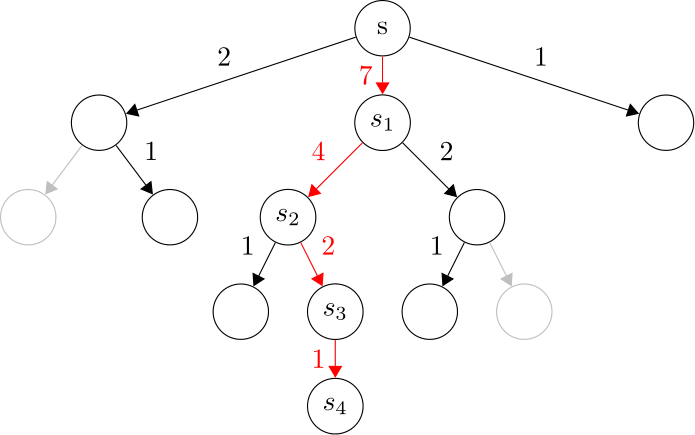

Here we define the principal variation $ s_{\text{seq}} $ to be the trajectory with the most visit count in the search tree. Fig. 2 shows an example of principal variation in MCTS. In this figure,

- each node is a game state,

- a parent node is connected to a child node via an edge,

- each edge is a legal action of the parent state,

- the number around each edge means the visit count of taking that action,

- the search depth $ k = 10 $,

- the principal variation $ s_{\text{seq}} = [s, s_{1}, s_{2}, s_{3}, s_{4}] $.

Training

AlphaGo Zero is trained by minimizing the following loss:

where

- $ p, v $ are the output policy and value of the network $ f $ (see Equation \ref{eq: network_alphago_zero}),

- $ z\in\{-1, 0, +1\} $ is the game result from the perspective of the current player,

- $ \pi $ is the probability distribution of the tree search,

- $ \theta_{1} $ is all parameters in the network $ f $,

- $ c $ is a L2 regularization constant.

Neural Networks that Learn from Planning

Now we want to leverage not only the probability distribution $ \pi $, but also some other valuable information from MCTS to benefit the agent. The question is: what kind of information is considered as valuable? A good choice would be the principal variation in MCTS since it predicts the most promising future state.

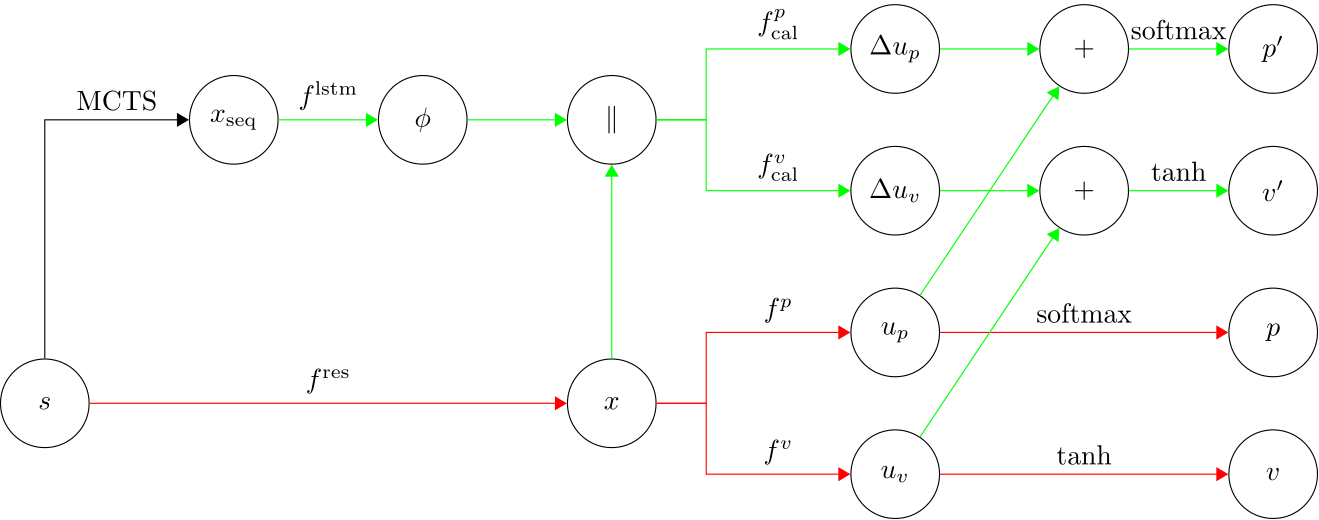

We modify the original AlphaGo Zero network so that the agent can learn from both the current state $ s $ and future predictions, see Fig. 3.

Principal variation $ s_{\text{seq}} $ can be collected from MCTS for each move in selfplay games. During training, principal variation $ s_{\text{seq}} $ is first encoded into a list of features $ x_{\text{seq}} $ before being fed into the neural network. Afterwards, we extract some contextual feature $ \phi $ from $ x_{\text{seq}} $ via a Long-Short Term Memory network (LSTM). Now we have both feature $ x $ and contextual feature $ \phi $. We simply concatenate them together and use them to calibrate the original policy and value estimation, which results in an improved policy and value estimation $ p’, v’ $.

To optimize those additional parameters $ \theta_{2} $ in the newly expanded network (shown as green edges in the above figure), we define a new loss $ L_{2} $:

Will this modification work? Well, it might work at first galance. However, it is not hard to see that the contextual feature $ \phi $ can only be obtained after MCTS. In other words, this modified network cannot be directly used to evaluate tree nodes during MCTS.

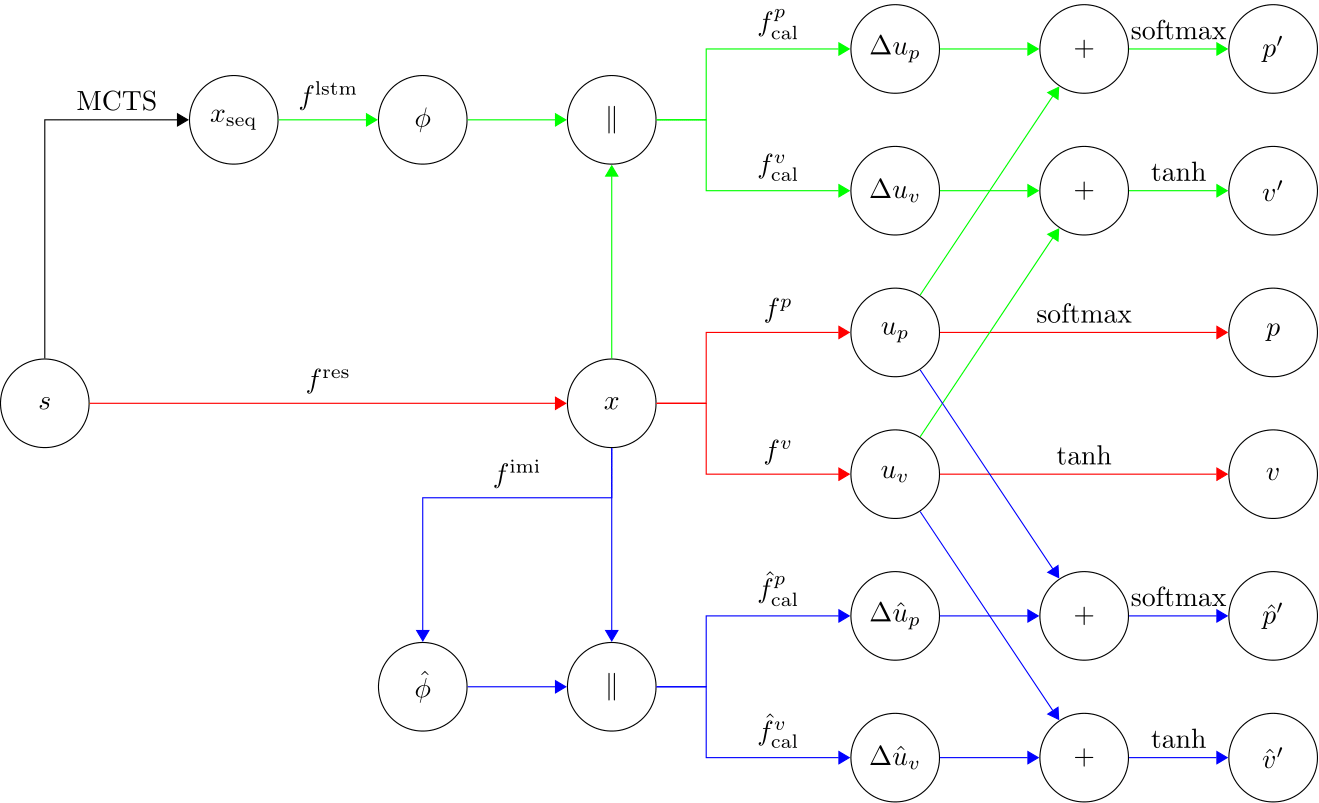

To compensate for this shortcoming, we further modify the network so that the agent can generate its own contextual feature $ \hat\phi $ without the help of MCTS, see Fig. 4.

We let the agent generate its own contextual feature $ \hat\phi $ directly from feature $ x $, under the condition that $ \hat\phi $ should be close to $ \phi $. In other words, $ \hat\phi $ functions as an imitation of $ \phi $. With both feature $ x $ and self-generated contextural feature $ \hat\phi $ at hand, we can calibrate the policy and value estimation in the same way as before, which yields an improved policy and value estimation $ \hat p’, \hat v’ $.

To optimize those additional parameters $ \theta_{3} $ in the latest expanded network (shown as blue edges in the above figure), we define a new loss $ L_{3} $:

With this modification, now the agent can provide a better estimation $ \hat p’, \hat v’ $ to evaluate tree nodes during MCTS, without having access to the actual principal variation $ s_{\text{seq}} $.

Experiments

Due to the very limited resources available and time limit for Master thesis, experiments have to be cut off half way. All experiments are conducted in $ 8\times 8 $ Othello.

General Statistics

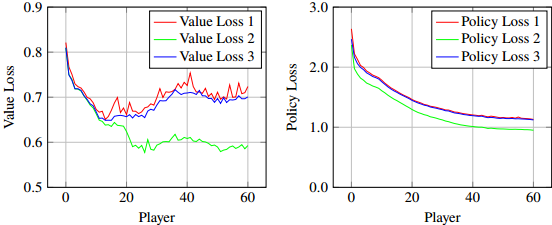

Fig. 5 shows the average training loss. Note that colors in Fig. 5 corresponds to colors in Fig. 4. As we can see,

- the basic estimation $ p, v $ (the red curves) has the highest error,

- the MCTS-based calibration $ p’, v’ $ (the green curves) has much lower error,

- the self-generated calibration $ \hat p’, \hat v’ $ (the blue curves) lies in the middle, closer to the basic estimation.

This result implies that combining feature $ x $ and contextual feature $ \phi $ together can significantly lower the prediction error. However, combinig feature $ x $ and imitation $ \hat\phi $ together only leads to a small improvement. This is probably because it is rather difficult for the network to imitate the non-static (continuously changing; not one-to-one mapping) contextural feature $ \phi $.

Gameplay Performance

We further measure the gameplay performance of the modified network in a couple of tournament games. We trained two different players for this purpose:

- challenger $ \alpha_{n} $

- based on the modified network,

- evaluate the tree nodes with $ \hat p’, \hat v’ $,

- search depth may vary.

- baseline player $ \beta_{n} $

- based on the AlphaGo Zero network,

- evaluate the tree nodes with $ p, v $,

- search depth is fixed to 100.

In those tournament games, challenger $ \alpha_{n} $ plays against baseline player $ \beta_{n} $, with $ n $ being the number of training iterations. For a fair competition, we choose players with the same number of training iterations.

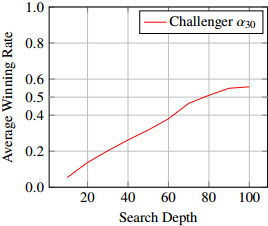

Fig. 6 records the average winning rate of the challenger $ \alpha_{30} $ against the baseline player $ \beta_{30} $ under different search depth. Note that both the Average Winning Rate and Search Depth are from the perspective of the challenger $ \alpha_{30} $.

We can see that the challenger $ \alpha_{30} $ wins about 56% of tournament games when both sides share the same search depth of 100. Equal playing strength is reached when the challenger only uses a search depth of 80. This result implies that the modified network can indeed improve the play strength.

Conclusion

I explored network architectures that can take advantage of future predictions from a local planner, which in return further helps planning. Experiment results show that the contextual feature $ \phi $ can significantly lower the prediction errors. However, the actual improvement is limited by the performance of $ \hat\phi $. Extracting better contextual feature $ \phi $, as well as learning better imitation $ \hat\phi $, should be an interesting topic for future work.

Anyway, this is just my Master thesis. Please do not take it too seriously.